Designing Optomechanical Parts to Minimize Stress on Optical Elements

Optomechanical systems often require the integration of delicate optical elements, such as lenses, mirrors, or prisms, into mechanical assemblies. A key challenge in designing these systems is ensuring that the mechanical interface does not induce stress in the optical components, as this can degrade optical performance or even lead to damage. This article outlines best practices for designing stress-minimized optomechanical interfaces, with examples to illustrate key concepts.

1. Understand the Optical Element’s Material Properties

Before designing the interface, it’s critical to consider the material properties of the optical element, including:

- Young’s Modulus: Determines how much the material deforms under stress. For example, fused silica has a relatively low Young’s modulus, making it more prone to deformation under load compared to sapphire.

- Thermal Expansion Coefficient (CTE): A mismatch in CTE between the optical element and its mount can lead to stress during temperature changes. For instance, BK7 glass (CTE ~7.1 × 10⁻⁶/K) mounted in an aluminum holder (CTE ~23 × 10⁻⁶/K) could lead to significant stress if the temperature varies significantly.

- Fracture Toughness: Indicates the material’s resistance to cracking under stress. Brittle materials like germanium require careful handling to avoid micro-cracks.

2. Opt for Kinematic Mounting Principles

Kinematic mounting minimizes stress by providing a well-defined yet compliant support system. The three fundamental kinematic constraints are:

- Three Points of Contact: Support the optical element on three points to avoid overconstraint. For example, a lens can rest on three small sapphire balls in a V-groove mount.

- Flexures or Pads: Use compliant materials or precision flexures to isolate the optical element from rigid mechanical constraints. A practical example is the use of silicone pads to hold a mirror, allowing slight deformation without transferring stress to the optic.

3. Match Thermal Expansion Coefficients

One of the most common causes of stress in optomechanical systems is thermal expansion mismatch. To mitigate this:

- Use materials with similar CTEs for both the optical element and its mount. For example, mounting fused silica optics in Invar holders (CTE ~1.2 × 10⁻⁶/K) minimizes thermal stress.

- For unavoidable mismatches, introduce flexible intermediate layers. For instance, use an RTV silicone adhesive layer to bond a BK7 lens to an aluminum mount, accommodating differential expansion.

4. Minimize Clamping Forces

Direct clamping can induce uneven stress. Instead, consider alternative retention methods:

- Edge Retention: Secure the optical element along its edge using soft pads or compliant rings. For example, a lens can be held with a retaining ring that includes a Teflon insert to distribute pressure evenly.

- Adhesive Mounting: Apply a uniform layer of adhesive that accommodates slight movements and distributes stress evenly. For instance, a small mirror in a laser system can be bonded using a thin layer of UV-curable adhesive.

5. Use Stress-Relief Features in the Mount

Mechanical mounts can be designed with features that relieve stress:

- Undercuts or Relief Grooves: Allow slight deformation of the mount to accommodate movements. For example, a mirror mount with grooves near the clamping edge can reduce stress concentrations.

- Floating Mounts: Incorporate ball-and-socket joints or gimbals that enable small angular adjustments without inducing stress. A common use case is in large telescope mirrors, where flexure mounts are used to handle thermal and gravitational deformations.

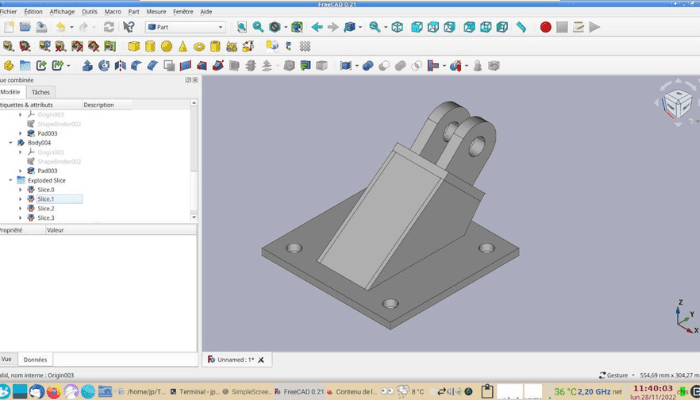

6. Implement Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

Before manufacturing, use FEA to simulate the stress distribution across the optical element and its interface. For example, simulate the deformation of a prism held in a steel mount under thermal cycling to ensure the stresses remain within acceptable limits.

7. Consider Environmental Factors

Environmental conditions, such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, and vibration, can significantly impact the performance of an optomechanical assembly. Design strategies include:

- Isolating Optical Elements from External Vibrations: Use dampers or vibration isolators. For instance, place a vibration-isolated platform under a sensitive interferometer to protect its optical components.

- Accounting for Thermal Cycling: Introduce compliant components that can expand or contract without stressing the optical element. A good example is using a polymer washer between a lens and its metal housing in outdoor applications.

8. Material Choices for Mounting Components

Selecting the right material for the mounting components is as important as the optical material itself. Consider:

- Low-outgassing materials to prevent contamination. For example, PEEK or anodized aluminum are commonly used in vacuum environments.

- Lightweight metals like aluminum or thermoplastics for reduced mass and stress on delicate optics. For instance, lightweight plastic mounts can hold small lenses in handheld devices.

- Titanium for its excellent balance of stiffness, thermal compatibility, and durability. A titanium mount is ideal for holding laser mirrors in high-stability setups.

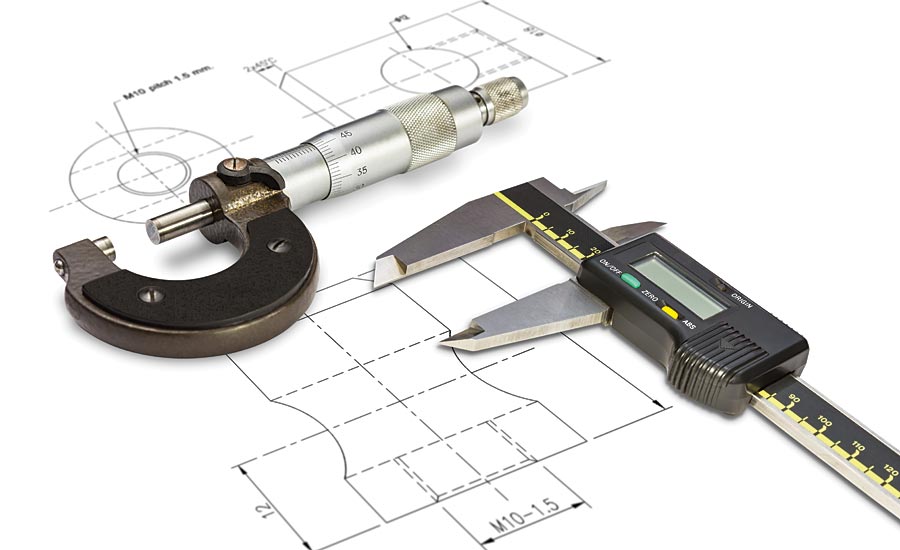

9. Testing and Prototyping

Finally, validate your design through physical testing. Mount the optical element and measure its performance under expected operating conditions. Examples include:

- Interferometric Testing: Detect stress-induced distortions in a mounted lens using a Zygo interferometer.

- Stress Birefringence: Use polarized light to check for stress patterns in a mounted optical window.

- Confocal Laser Microscopy: Analyze the surface of a mounted mirror for stress-induced changes in its flatness.

Conclusion

Designing optomechanical parts that interface with optical elements without inducing stress requires a deep understanding of material properties, precision engineering, and environmental considerations. By following best practices such as kinematic mounting, thermal matching, and iterative testing, you can achieve robust, stress-free integration of optical elements into your systems. This ensures optimal performance and long-term reliability for both precision instruments and industrial applications.

Cover photo source: arizona.edu